This story is part of Degrees Of Change[1], a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here[2].

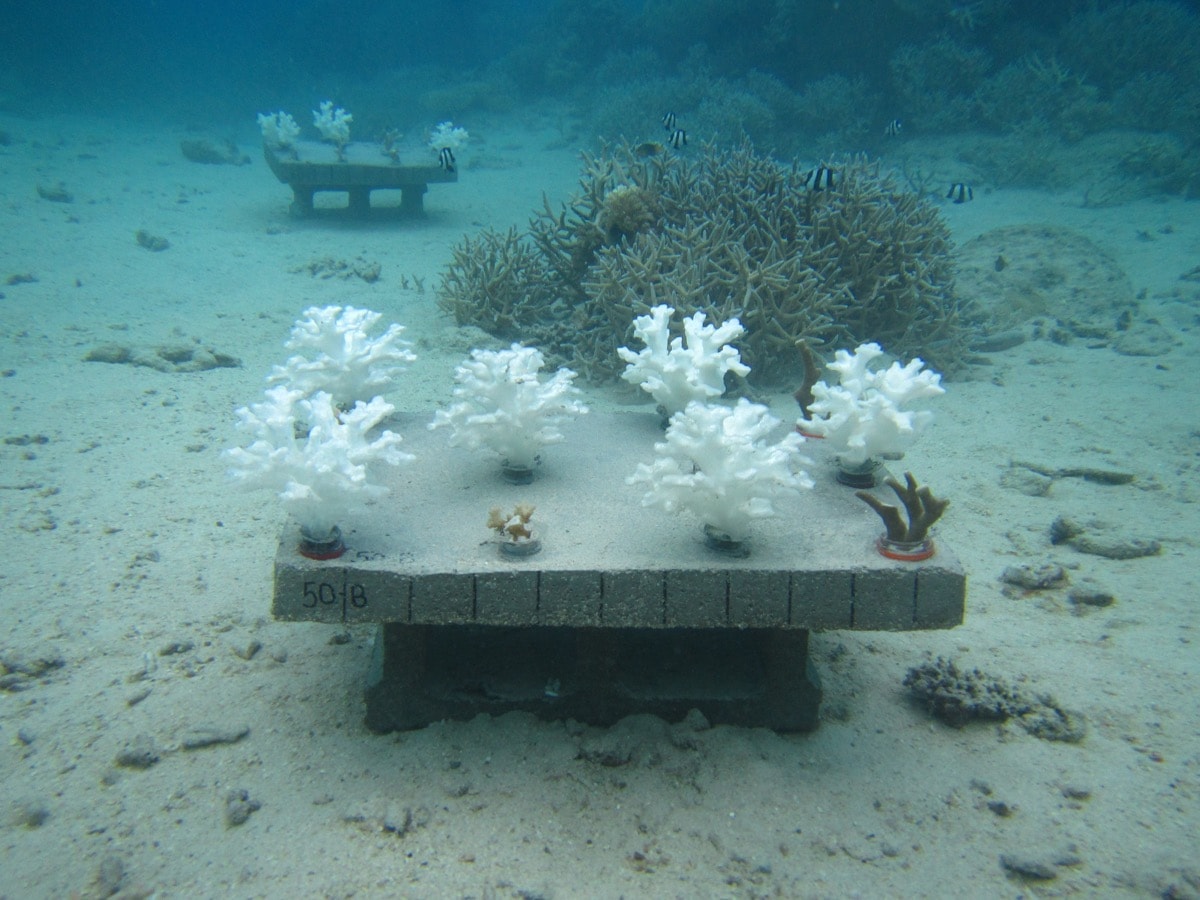

A quarter of the world’s corals are now dead, victims of warming waters, changing ocean chemistry, sediment runoff, and disease. Many spectacular, heavily-touristed reefs have simply been loved to death.

But there are reasons for hope. Scientists around the world working on the front lines of the coral crisis have been inventing creative solutions that might buy the world’s reefs a little time.

Restoration And Resilience

Crawford Drury and his colleagues at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology are working to engineer more resilient corals, using a coral library for selective breeding experiments, and subjecting corals to different water conditions to see how they’ll adapt.

Some resilient corals are still in the wild, waiting to be found. Narrissa Spiers of the Kewalo Marine Laboratory in Honolulu found one such specimen hiding out in the polluted Honolulu Harbor.

“No self respecting coral would ever want to live there, [so] it’s sort of a hotbed of evolution,” Spiers says.

Other scientists, like Danielle Dixson of the University of Delaware, are experimenting with corals that aren’t alive at all—3D-printed corals. The idea, she says, is to provide a sort of temporary housing for reef-dwellers after a big storm or human damage. Dixson likens these 3D-printed structures to the FEMA trailers brought in after a hurricane.

“In order for rebuilding to happen, you need people to live there so they can do their jobs,” she says. “The same thing is true in a reef.”

Dixson’s team is experimenting with these artificial corals in Fiji, to determine which animals use them as housing, and whether they spur the growth of new live corals too.

Two huge challenges remain. For any of these technologies to work at scale, we need quicker, more efficient ways to plant corals in the wild, says Tom Moore, the coral reef restoration lead at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“We can create the most super coral in the world,” Moore says. “But if we can’t swamp the system with them, it’s not going to work.”

Crawford Drury, the scientist who’s engineering corals at the lab in Hawaii, pointed out that none of this will work if we don’t act now to address climate change.

“We can’t create corals that can survive in a hot tub.”

What You Said

As we were producing this chapter of Degrees of Change, we asked you on the SciFri VoxPop app[3] to share your stories about how corals have changed over the years, too—and here’s what you had to say.

Andrea Corona, digital intern at SciFri, had this to say:

As a child growing up in Puerto Rico, marine wildlife and coral reef conservation was an everyday topic. My dad would take us snorkeling often, and there were many rules discussed before heading into the water. “We’re going into their world,” he would say, making sure to remind us not to touch, bother, or take anything out of its natural habitat. Today, when I return to these places I remember so bright and vividly in my memory, I notice they’re fading fast—but I’m hopeful that restoration efforts will bring back some colors into this fading, beautiful world.

Something You Can Do!

If you are planning on taking a snorkeling trip anytime soon, there are a few things you can do to reduce your impact on these delicate environments.

To start, make sure to use reef-safe sunscreen free of oxybenzone and other harmful chemicals that can lead to coral bleaching. You can check this list of known pollutants and see if your sunscreen contains any known pollutants. You can also protect yourself from the sun in other ways, by wearing shirts, hats, or apparel. Behavioral ecologist Danielle Dixon suggests using rash guard, “that way you are not releasing any chemicals,” she says.[4]

Another relatively easy thing she recommends is to avoid peeing in the water in heavily touristed reef areas. When you pee in the water, and everyone else does too, it increases the amount of nitrates and ammonia, affecting pH levels near you, and could make corals more susceptible to disease. Don’t pee in the water.

If you live near the coast, researcher Narissa Spies recommends doing what you can to lower local stresses. One way to do this is to reduce soil runoff, which is harmful for reefs. Not only does increased sediment and turbidity reduce light availability for coral and seagrass photosynthesis, it also smothers the organism. By planting grass or other ground cover in any bare spots in your lawn, you can make a big difference.

If you’d like to be more hands-on and involved in the conservation of reefs, you could volunteer your time to restoration efforts. There are plenty of ongoing projects accepting volunteers. “I would tell people to go on google, search, “coral reef restoration,” and you will be presented with a variety of organizations,” says Tom Moore, coral reef restoration lead at NOAA. Here’s some resources he shared with us: the Southeast Florida Action Network works with citizen volunteers to help report coral disease, the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Volunteer Program, Protected Resources Volunteer Opportunities.[5][6][7]

Because coral reef decline is one symptom in the larger illness of climate change, you can still have an impact even if you don’t live anywhere near the coast. By switching to renewable energy sources and reducing your carbon footprint, you are also helping.

Further Reading

Segment Guests

Tom Moore is Coral Reef Restoration Lead for NOAA in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Danielle Dixson is a behavioral ecologist and an associate professor at the University of Delaware in Lewes, Delaware.

Crawford “Ford” Drury is coral biology research program manager at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology in Kaneohe, Hawaii.

Narrissa Spies is a researcher in the Kewalo Marine Laboratory in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Meet the Producers and Host

About Christopher Intagliata[9]

@cintagliata[10]Christopher Intagliata is Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.

About Andrea Corona[11]

@amoniquecorona[12]Andrea Corona is a science writer and Science Friday’s fall 2019 digital intern. Her favorite conversations to have are about tiny houses, earth-ships, and the microbiome.

About Ira Flatow[13]

@iraflatow[14]Ira Flatow is the host and executive producer of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.

References

- ^ Degrees Of Change (sciencefriday.com)

- ^ here (sciencefriday.com)

- ^ SciFri VoxPop app (www.sciencefriday.com)

- ^ this list (haereticus-lab.org)

- ^ to help report coral disease (floridadep.gov)

- ^ the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Volunteer Program (coralreef.noaa.gov)

- ^ Protected Resources Volunteer Opportunities (www.fisheries.noaa.gov)

- ^ Donate (www.sciencefriday.com)

- ^ Christopher Intagliata (www.sciencefriday.com)

- ^ @cintagliata (twitter.com)

- ^ Andrea Corona (www.sciencefriday.com)

- ^ @amoniquecorona (twitter.com)

- ^ Ira Flatow (www.sciencefriday.com)

- ^ @iraflatow (twitter.com)

Reviewed by Medioblog

on

2:54 AM

Rating:

Reviewed by Medioblog

on

2:54 AM

Rating:

No comments: